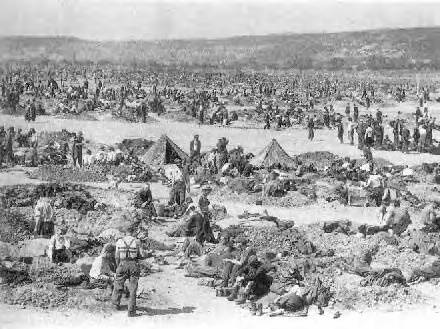

Zustände in den Lagern

Die Zustände in den Lagern dürften hinreichend bekannt sein, dennoch seien die wichtigsten Fakten wiederholt:

Die Gefangenen werden weder bei Einlieferung noch während des Aufenthaltes registriert.

Die Lager werden von allen Seiten bewacht, nachts mit Flutlicht. Fluchtversuche haben sofortige Erschießung zur Folge.

Zuweilen wird auch ohne ersichtlichen Anlaß in die Menge der Gefangenen geschossen.

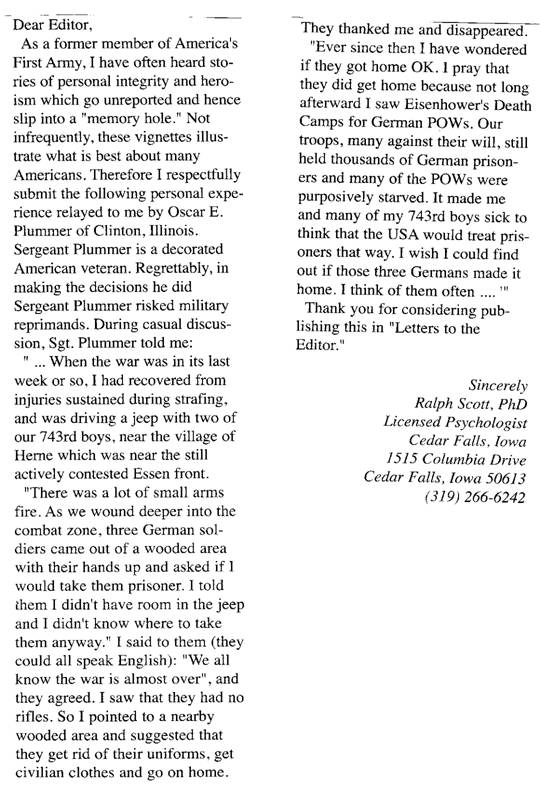

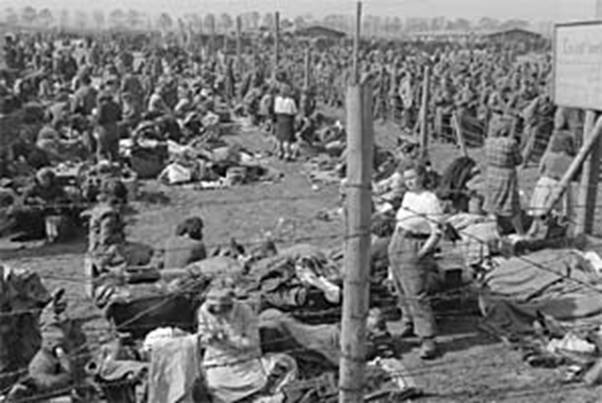

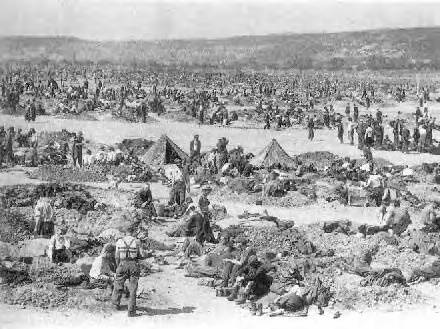

Lagergelände in den Rheinwiesen. Auch Frauen waren unter den Gefangenen.

Die Gefangenen hausen trotz Kälte, Regen und Schneeregen ohne Obdach auf nacktem Boden, der sich mit der Zeit in eine unergründliche Schlammwüste verwandelt. Unterkünfte zu errichten, ist verboten. Zelte werden nicht ausgegeben, obwohl sie in den Depots der deutschen Wehrmacht und in denen der US-Armee reichlich vorhanden sind.

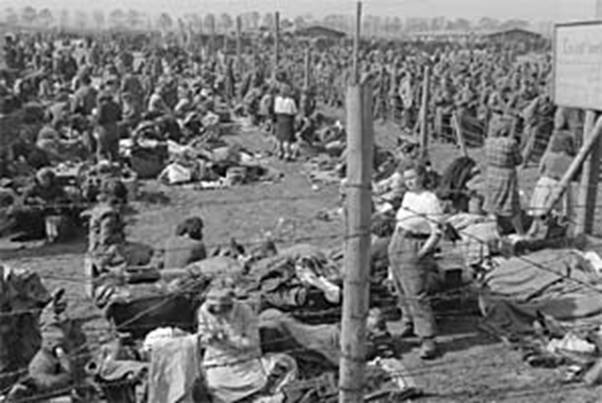

In den Rheinwiesen gefangen

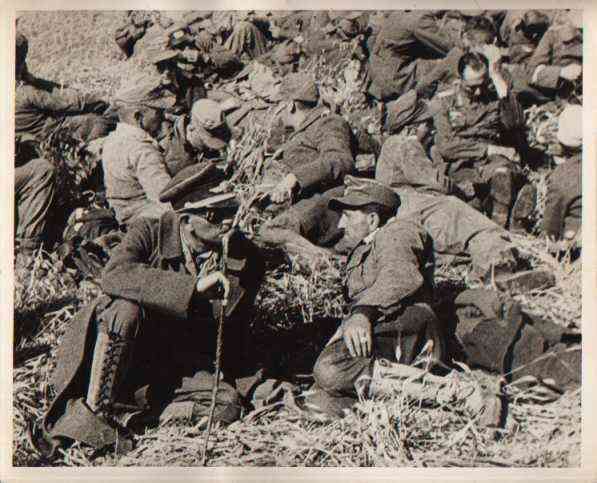

Die Gefangenen graben sich Erdlöcher, um vor der schlimmsten Kälte geschützt zu sein. Auch das wird immer wieder untersagt, so daß die Gefangenen oft gezwungen sind, die Erdlöcher zuzuschütten. Es geschieht, daß Bulldozer durch die Lager fahren und Erdlöcher samt den darin vegetierenden Gefangenen zuwalzen.

Waschgelegenheiten fehlen. Latrinen, über Gruben gelegte Balken, werden meist in der Nähe der Zäune angelegt, so daß die diesbezüglichen Vorgänge von außen einsehbar sind.

Während der ersten Zeit gibt es weder Nahrung noch Wasser, obwohl die erwähnten deutschen und amerikanischen Depots überreich mit Vorräten gefüllt sind und der Rhein Hochwasserstand hat. Um die deutschen Depots zu leeren, werden sie der Bevölkerung zur Plünderung überlassen.

Später erhalten die Gefangenen aus den

US-Vorräten: Eipulver, Milchpulver, Kekse. Blockschokolade, Kaffeepulver, jedoch noch immer kaum Wasser, so daß zu dem Hunger schwere Darmerkrankungen hinzukommen.

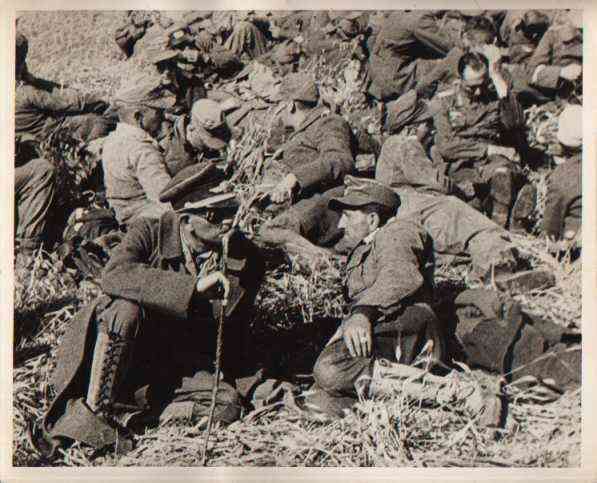

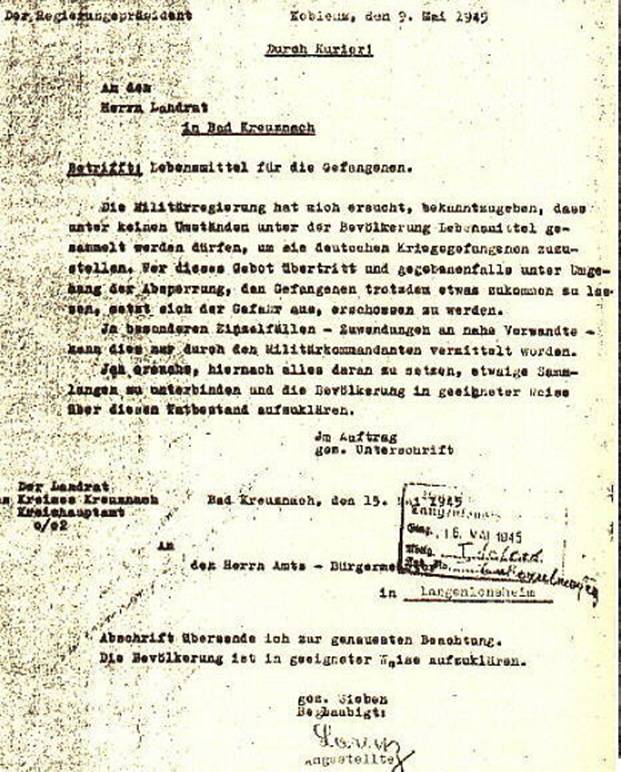

Die Gefangenen haben keinerlei Verbindung zur Außenwelt, Postverkehr findet nicht statt. Der Bevölkerung ist bei Todesstrafe verboten, die Gefangenen mit Nahrung zu versorgen.

Die deutschen Behörden werden angewiesen, die Bevölkerung entsprechend zu instruieren.

Wer dennoch versucht, den hungernden Gefangenen über den Lagerzaun etwas zukommen zu lassen, wird vertrieben oder erschossen.

Das Internationale Rote Kreuz hat keinen Zutritt zu den Lagern. Nahrungsmittel und Hilfsgüter, welche das Schweizer Rote Kreuz in Eisenbahnwaggons an den Rhein transportieren läßt, werden auf Befehl Eisenhowers zurückgeschickt.

Schwerkranke und Sterbende werden unzureichend oder überhaupt nicht versorgt, während nahe gelegene Krankenhäuser und Lazarette ungenutzt bleiben.

Als Wachpersonal werden z. T. entlassenen Fremdarbeiter eingestellt. Lagerpolizei besteht u. a. aus ehemaligen Häftlingen der Wehrmacht, z. B. aus den Häftlingen des deutschen Militärzuchthauses Torgau. Willkürliche Mißhandlungen der Gefangenen sind an der Tagesordnung. Es wird ihnen kein Einhalt geboten.

******

Zur umfassenden Information über die 'Rheinwiesenlager' sei auf das Standardwerk des Kanadiers James Bacque, Der geplante Tod, 8. Auflage, Berlin, 1999, hingewiesen.

Zwei von Bacque zitierte Erlebnisberichte mögen die Zustände in den Rheinwiesenlagern noch verdeutlichen.

Zwei Amerikaner berichten:

Der 30. April (1945) war ein stürmischer Tag. Regen, Schneeregen und Schnee wechselten sich ab, ein bis auf die Knochen durchdringender kalter Wind fegte von Norden her über die Ebenen des Rheintals dorthin, wo sich (das Lager) befand. Eng zusammengedrängt, um sich gegenseitig zu wärmen, bot sich den Blicken auf der anderen Seite des Stacheldrahts ein tief erschreckender Anblick dar: nahezu 100 000 ausgemergelte, apathische, schmutzige, hagere Männer mit leerem Blick, bekleidet mit schmutzigen, feldgrauen Uniformen, knöcheltief im Schlamm stehend. Hier und da sah man schmutzig weiße Flecken. Bei genauerem Hinsehen erkannte man, daß es sich um Männer mit verbundenem Kopf und verbundenen Armen handelte, oder Männer, die da in Hemdsärmeln standen! Der deutsche Divisionskommandeur berichtete, daß die Männer seit mindestens zwei Tagen noch nichts gegessen hätten und daß die Beschaffung von Wasser ein Hauptproblem sei - dabei war der Rhein, der hohen Wasserstand führte, nur 200 Meter entfernt.

(zitiert nach James Bacque, a.a.O., S. 51 f.)

Ein weiterer Amerikaner berichtet:

Ein Gefangener berichtet:

Im April wurden Hunderttausende von deutschen Soldaten sowie Kranke aus Hospitälern, Amputierte, weibliche Hilfskräfte und Zivilisten gefangengenommen....Ein Lagerinsasse von Rheinberg war über 80 Jahre alt, ein anderer war neun Jahre alt....andauernder Hunger und quälender Durst waren ihre Begleiter, und sie starben an Ruhr. Ein grausamer Himmel übergoß sie Woche für Woche mit strömendem Regen.....Amputierte schlitterten wie Amphibien durch den Matsch, durchnäßt und fröstelnd....Ohne Obdach tagaus, tagein und Nacht für Nacht lagen sie entmutigt im Sand von Rheinberg oder sie entschliefen in ihren zusammenfallenden Löchern....

(Heinz Janssen, Kriegsgefangener in Rheinberg, zitiert nach James Baque a.a.O., S. 52)

Inzwischen liegt auch eine wissenschaftliche Darstellung der Rheinwiesenlager vor.

Auch in den USA gibt es die Suche nach den Fakten.

Ein Augenzeuge berichtet:

http://www.the7thfire.com/Politics%20and%20History/us_war_crimes/Eisenhowers_death_camps.htm

In late March or early April, 1945, I was sent to guard a POW camp near Andernach along the Rhine. I had four years of high school German, so I was able to talk to the prisoners, although this was forbidden. Gradually, however, I was used as an interpreter and asked to ferret out members of the S.S. (I found none.)

Hausen in den Rheinwiesen

In Andernach about 50,000 prisoners of all ages were held in an open field surrounded by barbed wire. The women were kept in a separate enclosure I did not see until later. The men I guarded had no shelter and no blankets; many had no coats. They slept in the mud, wet and cold, with inadequate slit trenches for excrement. It was a cold, wet spring and their misery from exposure alone was evident.

Even more shocking was to see the prisoners throwing grass and weeds into a tin can containing a thin soup. They told me they did this to help ease their hunger pains. Quickly, they grew emaciated. Dysentery raged, and soon they were sleeping in their own excrement, too weak and crowded to reach the slit trenches. Many were begging for food, sickening and dying before our eyes. We had ample food and supplies, but did nothing to help them, including no medical assistance.

Outraged, I protested to my officers and was met with hostility or bland indifference. When pressed, they explained they were under strict orders from "higher up." No officer would dare do this to 50,000 men if he felt that it was "out of line," leaving him open to charges. Realizing my protests were useless, I asked a friend working in the kitchen if he could slip me some extra food for the prisoners. He too said they were under strict orders to severely ration the prisoners' food and that these orders came from "higher up." But he said they had more food than they knew what to do with and would sneak me some.

When I threw this food over the barbed wire to the prisoners, I was caught and threatened with imprisonment. I repeated the "offense," and one officer angrily threatened to shoot me. I assumed this was a bluff until I encountered a captain on a hill above the Rhine shooting down at a group of German civilian women with his .45 caliber pistol. When I asked, Why?," he mumbled, "Target practice," and fired until his pistol was empty. I saw the women running for cover, but, at that distance, couldn't tell if any had been hit.

This is when I realized I was dealing with cold-blooded killers filled with moralistic hatred. They considered the Germans subhuman and worthy of extermination; another expression of the downward spiral of racism. Articles in the G.I. newspaper, Stars and Stripes, played up the German concentration camps, complete with photos of emaciated bodies; this amplified our self-righteous cruelty and made it easier to imitate behavior we were supposed to oppose. Also, I think, soldiers not exposed to combat were trying to prove how tough they were by taking it out on the prisoners and civilians.

These prisoners, I found out, were mostly farmers and workingmen, as simple and ignorant as many of our own troops. As time went on, more of them lapsed into a zombie-like state of listlessness, while others tried to escape in a demented or suicidal fashion, running through open fields in broad daylight towards the Rhine to quench their thirst. They were mowed down. Some prisoners were as eager for cigarettes as for food, saying they took the edge off their hunger. Accordingly, enterprising G.I. "Yankee traders" were acquiring hordes of watches and rings in exchange for handfuls of cigarettes or less. When I began throwing cartons of cigarettes to the prisoners to ruin this trade, I was threatened by rank-and-file G.I.s too.

The only bright spot in this gloomy picture came one night when I was put on the "graveyard shift," from two to four A.M. Actually, there was a graveyard on the uphill side of this enclosure, not many yards away. My superiors had forgotten to give me a flashlight and I hadn't bothered to ask for one, disgusted as I was with the whole situation by that time. It was a fairly bright night and I soon became aware of a prisoner crawling under the wires towards the graveyard. We were supposed to shoot escapees on sight, so I started to get up from the ground to warn him to get back. Suddenly I noticed another prisoner crawling from the graveyard back to the enclosure. They were risking their lives to get to the graveyard for something; I had to investigate.

When I entered the gloom of this shrubby, tree-shaded cemetery, I felt completely vulnerable, but somehow curiosity kept me moving. Despite my caution, I tripped over the legs of someone in a prone position. Whipping my rifle around while stumbling and trying to regain composure of mind and body, I soon was relieved I hadn't reflexively fired. The figure sat up. Gradually, I could see the beautiful but terror-stricken face of a woman with a picnic basket nearby. German civilians were not allowed to feed, nor even come near the prisoners, so I quickly assured her I approved of what she was doing, not to be afraid, and that I would leave the graveyard to get out of the way.

I did so immediately and sat down, leaning against a tree at the edge of the cemetery to be inconspicuous and not frighten the prisoners. I imagined then, and still do now, what it would be like to meet a beautiful woman with a picnic basket, under those conditions as a prisoner. I have never forgotten her face.

Eventually, more prisoners crawled back to the enclosure. I saw they were dragging food to their comrades and could only admire their courage and devotion.

On May 8, V.E. Day, I decided to celebrate with some prisoners I was guarding who were baking bread the other prisoners occasionally received. This group had all the bread they could eat, and shared the jovial mood generated by the end of the war. We all thought we were going home soon, a pathetic hope on their part. We were in what was to become the French zone, where I soon would witness the brutality of the French soldiers when we transferred our prisoners to them for their slave labor camps. On this day, however, we were happy.

As a gesture of friendliness, I emptied my rifle and stood it in the corner, even allowing them to play with it at their request! This thoroughly "broke the ice," and soon we were singing songs we taught each other or I had learned in high school German ("Du, du liegst mir im Herzen"). Out of gratitude, they baked me a special small loaf of sweet bread, the only possible present they had left to offer. I stuffed it in my "Eisenhower jacket" and snuck it back to my barracks, eating it when I had privacy. I have never tasted more delicious bread, nor felt a deeper sense of communion while eating it. I believe a cosmic sense of Christ (the Oneness of all Being) revealed its normally hidden presence to me on that occasion, influencing my later decision to major in philosophy and religion.

Shortly afterwards, some of our weak and sickly prisoners were marched off by French soldiers to their camp. We were riding on a truck behind this column. Temporarily, it slowed down and dropped back, perhaps because the driver was as shocked as I was. Whenever a German prisoner staggered or dropped back, he was hit on the head with a club until he died. The bodies were rolled to the side of the road to be picked up by another truck. For many, this quick death might have been preferable to slow starvation in our "killing fields."

When I finally saw the German women in a separate enclosure, I asked why we were holding them prisoner. I was told they were "camp followers," selected as breeding stock for the S.S. to create a super-race. I spoke to some and must say I never met a more spirited or attractive group of women. I certainly didn't think they deserved imprisonment.

I was used increasingly as an interpreter, and was able to prevent some particularly unfortunate arrests. One rather amusing incident involved an old farmer who was being dragged away by several M.P’s. I was told he had a "fancy Nazi medal," which they showed me. Fortunately, I had a chart identifying such medals. He'd been awarded it for having five children! Perhaps his wife was somewhat relieved to get him "off her back," but I didn't think one of our death camps was a fair punishment for his contribution to Germany. The M.P.s agreed and released him to continue his "dirty work."

Famine began to spread among the German civilians also. It was a common sight to see German women up to their elbows in our garbage cans looking for something edible -- that is, if they weren't chased away.

When I interviewed mayors of small towns and villages, I was told their supply of food had been taken away by "displaced persons" (foreigners who had worked in Germany), who packed the food on trucks and drove away. When I reported this, the response was a shrug. I never saw any Red Cross at the camp or helping civilians, although their coffee and doughnut stands were available everywhere else for us. In the meantime, the Germans had to rely on the sharing of hidden stores until the next harvest.

Hunger made German women more "available," but despite this, rape was prevalent and often accompanied by additional violence. In particular I remember an eighteen-year old woman who had the side of her faced smashed with a rifle butt and was then raped by two G.I.s. Even the French complained that the rapes, looting and drunken destructiveness on the part of our troops was excessive. In Le Havre, we'd been given booklets warning us that the German soldiers had maintained a high standard of behavior with French civilians who were peaceful, and that we should do the same. In this we failed miserably.

"So what?" some would say. "The enemy's atrocities were worse than ours." It is true that I experienced only the end of the war, when we were already the victors. The German opportunity for atrocities had faded; ours was at hand. But two wrongs don't make a right. Rather than copying our enemy’s crimes, we should aim once and for all to break the cycle of hatred and vengeance that has plagued and distorted human history. This is why I am speaking out now, forty-five years after the crime. We can never prevent individual war crimes, but we can, if enough of us speak out, influence government policy. We can reject government propaganda that depicts our enemies as subhuman and encourages the kind of outrages I witnessed. We can protest the bombing of civilian targets, which still goes on today. And we can refuse ever to condone our government's murder of unarmed and defeated prisoners of war.

I realize it is difficult for the average citizen to admit witnessing a crime of this magnitude, especially if implicated himself. Even G.I’s sympathetic to the victims were afraid to complain and get into trouble, they told me. And the danger has not ceased. Since I spoke out a few weeks ago, I have received threatening calls and had my mailbox smashed. But its been worth it. Writing about these atrocities has been a catharsis of feeling suppressed too long, a liberation, and perhaps will remind other witnesses that "the truth will make us free, have no fear." We may even learn a supreme lesson from all this: only love can conquer all.

Source: Reprinted from The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 161-166

http://www.the7thfire.com/Politics%20and%20History/us_war_crimes/Eisenhowers_death_camps.htm

Siehe auch:

http://www.thetruthseeker.co.uk/article.asp?id=136

http://www.thetruthseeker.co.uk/article.asp?id=135

http://www.rense.com/general46/germ.htm

Die Fakten zeigen, daß die Zustände in den Rheinwiesenlagern nicht auf dem oft behaupteten Unvermögen der Amerikaner beruhen, mit der Masse der Gefangenen fertigzuwerden. Die Zustände samt dem zwangsläufig daraus resultierenden sind gewollt.

James Bacque bestätigt, daß General Dwight Eisenhower für die Zustände verantwortlich ist:

Die Verantwortung für die Behandlung der deutschen Kriegsgefangenen in amerikanischer Hand lag bei den Kommandeuren der US Army in Europa, untergeordnet nur der politischen Kontrolle durch die Regierung. Alle Entscheidungen über Gefangenenbehandlung wurden tatsächlich allein von der US Army in Europa getroffen...

(Bacque, a.a.O., S. 45)

Dr. Ernest F. Fisher jun., Oberst der Armee der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika, schreibt:

Eisenhowers Haß, toleriert von einer ihm gefügigen Militärbürokratie, erzeugte diesen Horror der Todeslager, der mit nichts in der amerikanischen Militärgeschichte vergleichbar ist. Angesichts der katastrophalen Folgen dieses Hasses ist die lässige Gleichgültigkeit, die die SHAEF-Offiziere (des Hauptquartiers der alliierten Expeditionskräfte) an den Tag legten, die schmerzlichste Seite der amerikanischen Verstrickung.

(zitiert nach Bacque, a.a.O., S. 17)

******

Im Juli 1945 werden mit Einrichtung der Besatzungszonen die Rheinwiesenlager je nach ihrer Lage den Briten oder den Franzosen übergeben. Die Briten versuchen, die Versorgung der Gefangenen zu bessern. Die Franzosen bessern nichts, sondern beginnen, die noch arbeitsfähigen Männer zur Zwangsarbeit nach Frankreich abzutransportieren. Die wenigsten kehren zurück.

weiter

zurück zur Startseite